I. Introduction: The Enduring Legacy of Wicha Sak Yant

Wicha Sak Yant (วิขา สักยันต์), a revered form of traditional tattooing prevalent across Southeast Asia, transcends mere aesthetic adornment to function as a profound conduit of mystical and spiritual energies. The term “Sak Yant” itself is etymologically derived from the Thai word “Sak” (สัก), signifying “to tap” or “to tattoo,” and the Sanskrit term “Yantra,” which denotes a “mystical diagram” or “instrument”. These intricate designs, frequently characterized by geometric patterns or zoomorphic representations, are invariably complemented by inscriptions in ancient scripts, which are believed to imbue the wearer with auspicious attributes such as prosperity, charisma, or formidable strength.

Beyond their visual appeal, Sak Yant are regarded as deeply sacred rituals, rather than conventional tattoos. Their application and subsequent spiritual efficacy are intrinsically linked to a meticulous process of ritualistic consecration and the recitation of sacred incantations by venerable Buddhist monks or rigorously trained lay masters. This profound spiritual dimension positions Sak Yant as a vital element within the cultural and religious landscape of Southeast Asia, offering recipients perceived protection, enhanced luck, and inner fortitude. The potency of these sacred markings is often understood to be contingent upon the wearer’s adherence to specific moral principles, known as Sila, which are closely aligned with the Five Precepts of Buddhism. Violation of these ethical guidelines is widely believed to diminish or entirely nullify the protective and beneficial powers of the tattoo.

A Lersi assists Ajarn Ord in the Conducting of the Preliminaries of Wai Kroo to the Gods of Sak Yant

This report endeavors to provide a comprehensive and academically rigorous examination of Wicha Sak Yant. It will explore its complex historical origins, tracing its evolution from ancient animistic practices through the influences of Indic traditions and the Khmer Empire, culminating in its formalized practice in Siam. Furthermore, this analysis will delineate the sacred modalities and ritualistic consecration processes, highlight the contributions of prominent masters, and meticulously explicate the diverse iconographic repertoire and the sacred scripts that underpin this enduring spiritual art form.

II. Historical Trajectories and Origins of Sak Yant

The historical development of Sak Yant is a complex tapestry woven from indigenous animistic beliefs, ancient Indic spiritual practices, and the profound influence of Buddhist and Hindu traditions.

A. Ancient Roots: Animism, Indic Yantras, and Early Syncretism

The genesis of Sak Yant traditions can be traced to indigenous tribal animism, characterized by early beliefs in various animal spirits and their associated powers. This foundational layer of spiritual practice provided a fertile ground for the later integration of more formalized religious systems. Sak Yant designs are fundamentally based on ancient Indic yantras, which are powerful mystical diagrams intended to ward off negative influences and invoke specific energies. The practice thus represents a profound hybridization, incorporating elements from Hindu, Animist, and Buddhist traditions. The evolution of Sak Yant over time mirrors broader transformations within the religious landscape of Thailand, reflecting a convergence where Theravada Buddhism absorbed and integrated elements from Animist and Hindu forms.

This syncretic foundation is a critical factor in the enduring power and adaptability of Sak Yant. By drawing upon multiple spiritual wellsprings, the practice is able to address a wide spectrum of human needs, ranging from protection against malevolent spirits to the accumulation of positive karmic benefits and the attainment of material success. This multifaceted appeal has enabled Sak Yant to remain robust and resilient across various cultural and religious shifts throughout history, distinguishing it from practices rooted in a singular, less adaptable spiritual framework. The inherent hybridity of Sak Yant allowed it to not only survive but also to flourish and evolve.

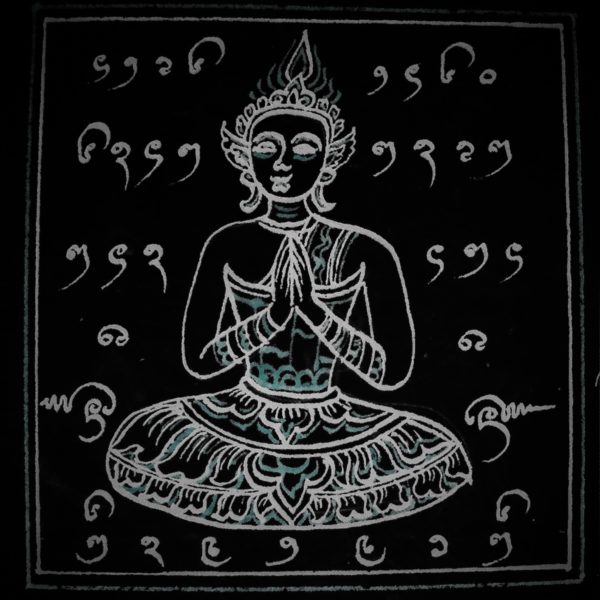

Putta Jao Prode Loke (Buddha Blessing the World Yantra). To wear this Yant as a tattoo or an amulet, brings different effects, depending on where you wear the Yantra.

B. The Khmer Empire: Cradle of Sak Yant and Documented Beginnings

The historical consensus suggests that Sak Yant originated within the Khmer Empire, which flourished from the 9th to the 15th centuries and encompassed significant portions of modern-day Thailand, Burma, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. Early evidence of practices akin to Sak Yant appears in historical records from this period, particularly noting warriors receiving protective tattoos prior to engaging in battle. Tangible proof of these early yantras can be observed in the carvings on the walls of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, dating back to the 12th century. The art of tattooing yantras, along with its specific designs, symbolism, and the use of ancient Khmer scripture, is understood to have originated within the Khmer Empire over a millennium ago.

The pervasive use of Sak Yant by warriors in the Khmer Empire and later in ancient Siam for protection and perceived invulnerability in combat highlights a significant functional demand that likely served as a catalyst for its proliferation. The constant state of warfare during these periods created an urgent need for both psychological and perceived physical safeguards. The belief that these tattoos could render warriors invisible or impervious to harm would have been an incredibly powerful motivator for both the masters who applied them and the soldiers who received them. This practical, life-preserving application firmly embedded Sak Yant within military culture, and by extension, facilitated its widespread adoption and continued evolution across broader societal strata.

C. Evolution in Siam: From Ayutthaya Warriors to Modern Practice

The earliest documented use of Sak Yant in what is now Thailand dates back to the 1600s, during the Ayutthaya Kingdom. Historical records from this era indicate that warriors were bestowed with yant tattoos and yant shirts, serving as talismans to safeguard them in battle. The tradition underwent further formalization during the Ayutthaya period (14th-18th centuries), a crucial phase where monk-scholars played a pivotal role in codifying the designs and practices. Prior to this, in the Sukhothai period (1347–1376 BE), an ancient inscription known as “Tua Tho,” associated with Lek Yant (sacred numerology), was discovered on silver palm leaf manuscripts, marking one of the earliest known instances of this practice in Thai history. The first explicit historical mention of Lek Yant in Thai chronicles dates to 1498 CE.

Historically, tattooing was a pervasive practice among men in Thailand, serving primarily as a sign of spiritual and religious faith rather than a mere artistic display. The popularity of Sak Yant subsequently grew significantly, particularly among soldiers and Muay Thai fighters, which ultimately contributed to its global recognition.

Historically, tattooing was a pervasive practice among men in Thailand, serving primarily as a sign of spiritual and religious faith rather than a mere artistic display. The popularity of Sak Yant subsequently grew significantly, particularly among soldiers and Muay Thai fighters, which ultimately contributed to its global recognition.

The formalization of Sak Yant in Siam, particularly during the Ayutthaya period, involved a deliberate interplay between state interests, the Sangha (Buddhist monastic community), and existing folk beliefs. The systematization of practices by monastic scholars indicates a strategic effort to integrate and legitimize indigenous magical traditions within the prevailing Theravada Buddhist framework, rather than suppressing them outright. This strategic absorption provided Sak Yant with broader societal acceptance and institutional support, ensuring its continuity and development within a burgeoning national religious identity. The later discontinuation of formal Khmer script education after 1945 further illustrates the influence of state policies on the linguistic aspects of the tradition, demonstrating how national identity and modernization efforts could shape even deeply entrenched cultural practices.

III. The Sacred Modalities and Ritualistic Consecration of Sak Yant

The application of Sak Yant is far removed from conventional tattooing; it is a meticulously observed sacred ritual, imbued with spiritual significance at every stage.

A. Traditional Application: Hand-Poked Techniques and Tools

Traditionally, Sak Yant are applied using a hand-poked method, utilizing either a metal stylus known as a Khem or a bamboo stick fitted with a needle. This technique stands in stark contrast to modern tattoo machines. The hand-poked method is not merely a historical artifact but an integral part of the ritual, serving as a test of endurance for the recipient. This physical discomfort is not incidental; it is understood as a reflection of Buddhist Dukkha (suffering), where the acceptance and transcendence of pain contribute to the tattoo’s spiritual purpose. The physical pain endured during the tattooing process is thus an integral, even sacramental, component of the ritual. It functions as a form of ascetic practice, enhancing the recipient’s commitment, focus, and spiritual receptivity, thereby amplifying the tattoo’s perceived magical potency. This emphasis on enduring discomfort distinctly differentiates traditional Sak Yant from Western tattooing practices, where pain is typically minimized. The choice between a bamboo rod, believed to cause less pain and promote faster healing due to its flexibility, and a steel rod, preferred for its precision and the sharpness of the resulting design despite being more painful, ultimately rests on personal preference and the master’s counsel.

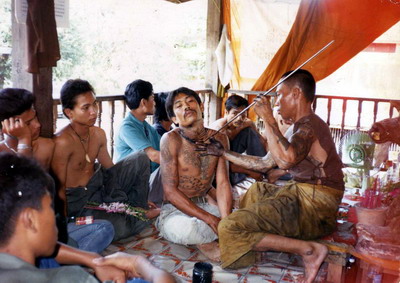

Spencer and Luang Pi Pant 1998

B. The Consecration Ritual: Chants, Blessings, and Spiritual Activation

The entire process of receiving a Sak Yant is a sacred ritual, typically performed by venerable Buddhist monks or highly trained lay masters, known as Ajarns. A crucial element of this ritual is the consecration, during which the master recites sacred chants, or mantras (Kathas), concurrently with the tattoo’s application. These incantations are believed to actively imbue the tattoo with spiritual potency, transforming it from a mere drawing into a living talisman. It is widely held that without this blessing ritual, the tattoo remains solely a design, devoid of any spiritual power. Furthermore, the master’s discernment, often described as an ability to “read the recipient’s aura,” guides the selection and placement of the design, ensuring its alignment with the specific boons or protections sought by the individual.

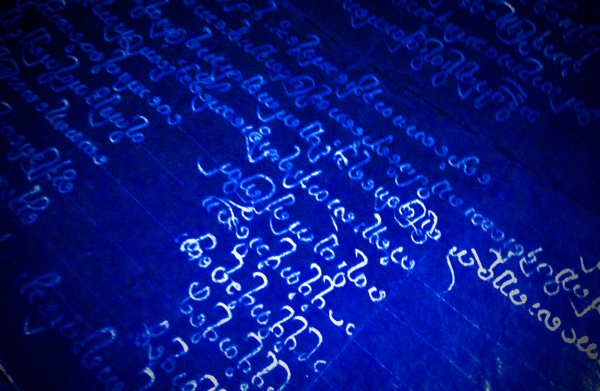

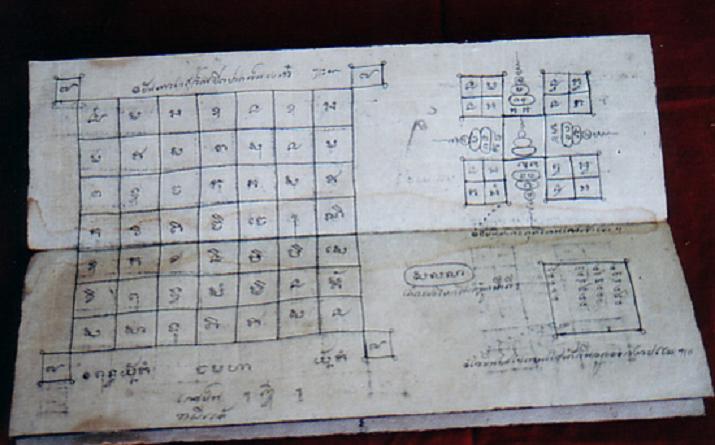

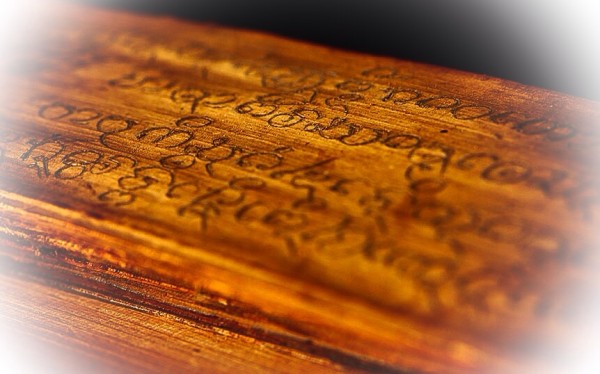

Sacred Kata Akom Incantations and Magical Instructions, in a Kampir Yant Samud Khoi – Black Parchment Occult Grimoire in Khom Lanna Sanskrit

The spiritual efficacy of Sak Yant is directly contingent upon the master’s ritualistic actions and their inherent spiritual power. The master functions as a spiritual conduit, channeling ancient knowledge and potent energies into the physical tattoo. This transformative act elevates the tattoo beyond mere pigment and design, rendering it a dynamic and potent talisman. This underscores the living and evolving nature of the tradition, where the spiritual attainment and ritualistic precision of the practitioner are paramount to the Sak Yant’s effectiveness.

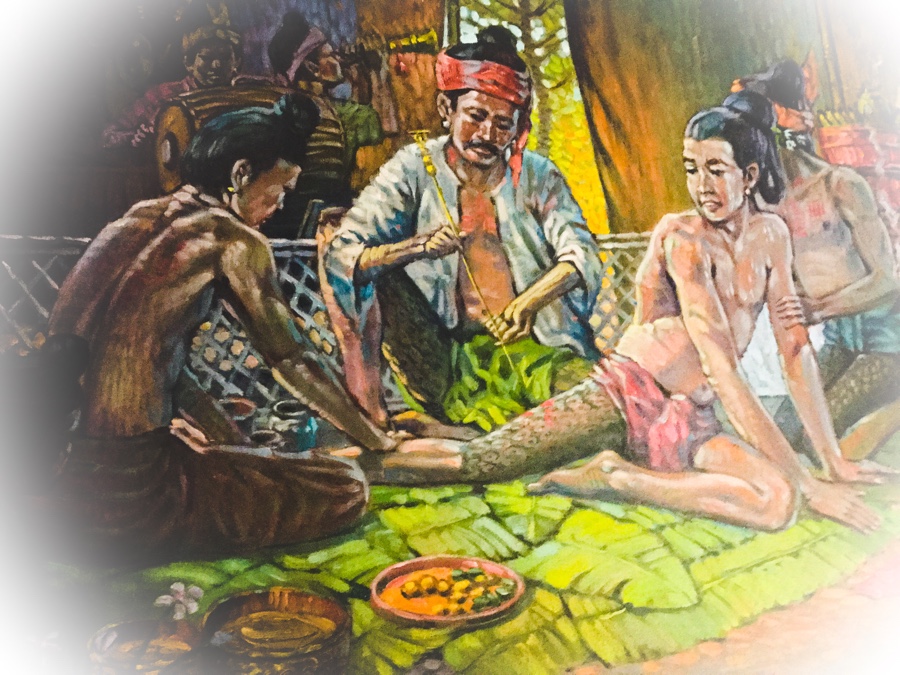

Ancient Sak Yant Scene – Original Painting property of Ajarn Spencer Littlewood

C. Ethical Imperatives: Sila, Observances, and the Recipient’s Commitment

A fundamental aspect of receiving a Sak Yant is the implicit commitment to a prescribed code of conduct. Recipients are generally expected to adhere to specific moral principles, known as Sila, which are closely analogous to the Five Precepts in Buddhism. These guidelines are considered essential for maintaining the tattoo’s power. It is widely believed that transgressions against these moral codes—such as killing, stealing, lying, engaging in sexual misconduct, intoxication, or speaking ill of parents or elders—will diminish or entirely nullify the tattoo’s protective and beneficial attributes.

Beyond these general precepts, more specific prohibitions may apply, including not spitting into toilets, avoiding sexual activity during a woman’s menstruation, refraining from drug use, abstaining from certain foods (such as zucchini, fang, and licorice), avoiding passing under clotheslines, or refraining from sitting on ceramic urns.

Khong Khuen during a Wai Kroo

The explicit linkage between the power of Sak Yant and the wearer’s adherence to moral precepts signifies that the practice extends beyond a transactional exchange of tattoo for power. Sak Yant thus functions not only as a protective talisman but also as a potent moral compass and a mechanism for behavioral reinforcement. The belief that the tattoo’s efficacy is directly tied to ethical conduct provides a strong incentive for recipients to cultivate a virtuous life, seamlessly integrating spiritual practice into their daily existence. This transforms the tattoo into a constant reminder of one’s commitment to Dhamma, fostering self-discipline and mindfulness, and thereby contributing to broader social cohesion and moral order within the community.

IV. Prominent Sak Yant Masters: Guardians of the Wicha

The perpetuation and evolution of Wicha Sak Yant are inextricably linked to the lineage and spiritual prowess of its masters, who comprise both ordained monks and lay practitioners.

A. The Role of Ordained Monks and Lay Masters (Ajarns, Ruesi)

Sak Yant has been traditionally applied by venerable Buddhist monks or by rigorously trained lay masters, known as Ajarns (อาจารย์). Ajarns are spiritual mentors possessing profound knowledge of magic and Buddhist principles; many are former monks who have transitioned to lay status. Another significant category of practitioners includes the Ruesi (พระฤษี), or hermit monks, who embody wisdom and power acquired through extensive spiritual knowledge, often depicted as traveling mystics. The transmission of this esoteric knowledge has historically occurred through direct teacher-student relationships, leading to the development of distinct lineages over many centuries.

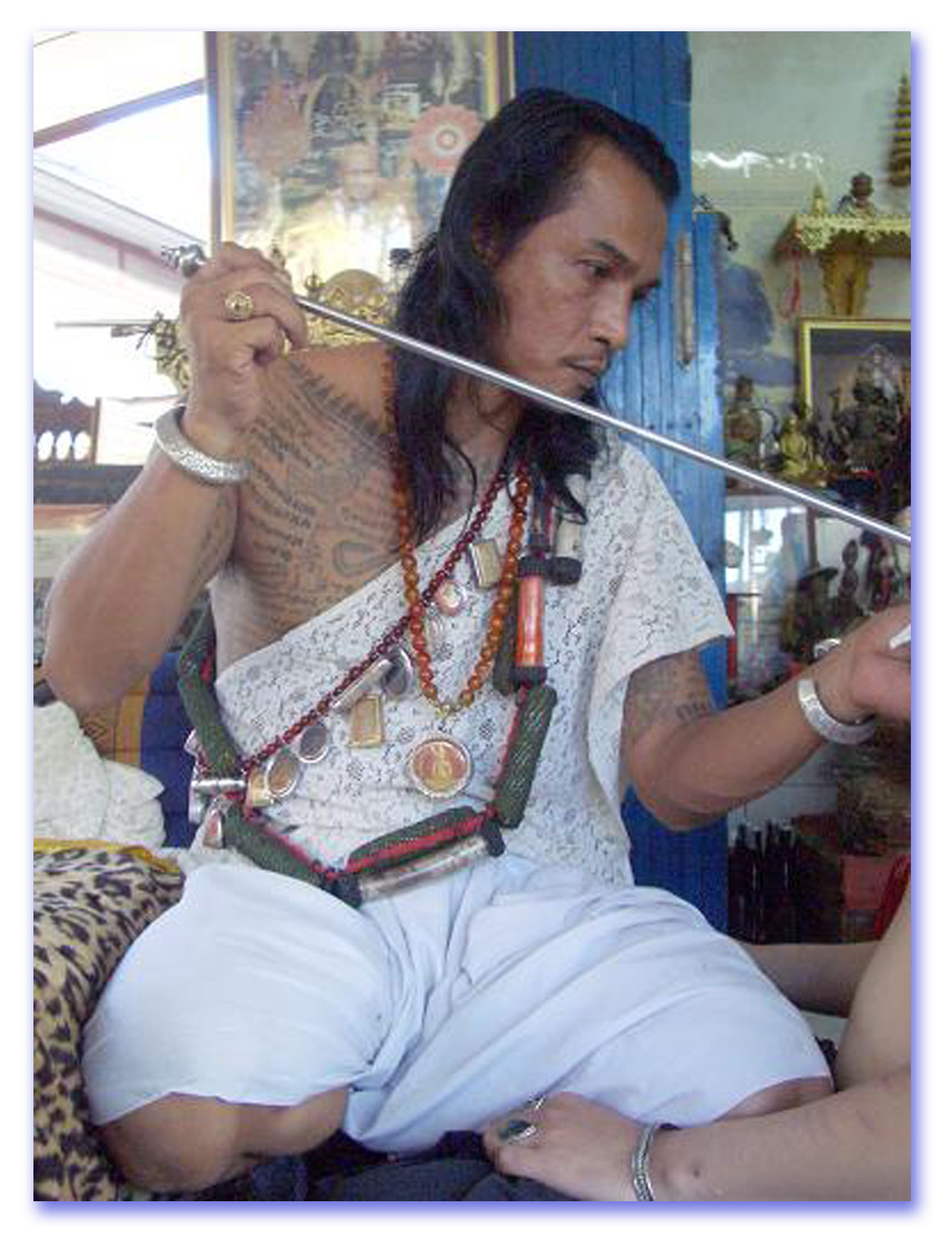

Ajarn Jiak Po Dam

B. Illustrious Masters of Old and Past

Several masters throughout history have significantly shaped the Wicha Sak Yant tradition:

- Luang Phor Pern (หลวงพ่อเปิ่น ฐิตคุโณ) of Wat Bang Phra: A highly revered monk, Luang Phor Pern is widely credited with substantially increasing the popularity and visibility of Sak Yant. Wat Bang Phra, located in Nakhon Pathom Province, remains one of the most significant temples for Sak Yant, hosting an annual festival where thousands gather to re-energize their tattoos. His lineage is particularly emphasized as a foundational tradition.

- Luang Por Lae (หลวงพ่อแล) of Wat Pra Song, Petchburi: Known for his profound expertise in Sak Yant and the creation of sacred amulets, Luang Por Lae’s mastery was cultivated under the tutelage of 14 esteemed Guru Master Ajarns. His dedication to acquiring potent Wicha was deeply influenced by a tragic personal event—the murder of his mother and siblings—which motivated him to seek magical knowledge for the protection of others. He was especially renowned for his unique formula of nine distinct types of Hanuman/Vanora Sak Yant.

- Luang Pu Suk (หลวงปู่ศุข) of Wat Pak Khlong Makham Thao, Chainat: A prominent figure before World War II, Luang Pu Suk was widely recognized for his expertise in mystical tattooing. His amulets and Yant shirts continue to be highly sought after. He was celebrated for his formidable psychic powers, particularly those developed through kasina meditation, and was a respected teacher to Prince Abhakara Kiartivongse, Prince of Chumphon.

- Luang Pu Thong (หลวงปู่ทอง) of Wat Ratchayotha, Bangkok: Considered an exceptionally skilled monk from ancient times, Luang Pu Thong was a junior disciple of Somdet Phra Puttajarn (To Phromrangsi). He gained renown for creating Yant shirts that were believed to render soldiers invulnerable, leading to the moniker “ghost soldiers” during wartime. His longevity, living to 117 years and observing 96 vassa (rains retreats), led him to be revered as an Arahant.

Luang Por Phern Wai Kroo at Samnak Sak Yant of Ajarn Ord

C. Contemporary Masters and Lineage Dynamics

The landscape of Sak Yant masters in the contemporary era reflects both traditional adherence and pragmatic adaptation. While some masters maintain strict adherence to specific lineages, a growing number of modern practitioners expand their knowledge by studying diverse traditions, transcending rigid lineage boundaries. This reflects a pragmatic adaptation to modern realities, including increased accessibility for foreign recipients and the formalization or regulation of monastic conduct. The shift of some masters from monkhood to lay Ajarn status, notably due to a government order prohibiting monks from tattooing , may lead to a diversification of practice. This could potentially make Sak Yant more accessible to a broader audience while simultaneously raising questions about authenticity and traditional adherence for some purists.

Ajarn Ord Kalasin (Looksit of Wat bang Pra Luang Por Phern lineage transmission)

Prominent contemporary Ajarns in Chiang Mai include Ajarn Dang, often referred to as a “Master’s Master” due to other Sak Yant practitioners seeking his training; Ajarn Sam, who transitioned from monkhood; Ajarn Beer, stemming from the renowned Wat Bang Phra tradition; multiple Ajarn Toms with diverse lineage knowledge; Ajarn Sak, with a background in Burmese magic; Ajarn K Munglanna; Ajarn Amnat, known for high hygiene standards; Arjan Inn Kham Pan Ya Reang, a Cambodian and Thai trained master who utilizes tattoo machines; Ajarn NanKhong, celebrated for his popular Samnak and quality work; and Ajarn Ton, another respected student of Wat Bang Phra.

Among contemporary monastic masters in Chiang Mai are Monk Rachon, a 4th-generation Sak Yant monk; Monk Eak, also a 4th-generation practitioner; Monk Aum, known for his Lanna style; Monk Eng, recognized for his expertise in Buddhist magic; and Monk Rung, who practices from his grandfather’s home.

Grandmaster Ajarn Pum in Bangkok exemplifies the breadth of contemporary mastery, having learned from over 70 masters and his own father before becoming a master in 2002. His decision to leave monkhood in 2018 was influenced by the need to care for his aging mother and a government decree that no longer permitted monks to perform tattooing, deeming it outside monastic duties. Despite this, he continues to practice as a revered Grandmaster, also offering services such as fortune-telling and Yantra mantra candle ceremonies.

V. The Iconographic Repertoire: Designs, Meanings, and Classifications

The visual language of Sak Yant is rich and complex, encompassing a diverse array of forms, symbols, and scripts, each imbued with specific meanings and spiritual purposes.

A. Typology of Yantras: Geometric, Animistic, Human, and Deity Portrayals

Yantras are typically characterized by geometric shapes that radiate concentrically from a central point, including triangles, circles, hexagons, octagons, and symbolic lotus petals. An outer square frequently represents the four cardinal directions. This structured typology suggests that Sak Yant operates on a principle of sacred geometry, where specific shapes and their arrangements are believed to inherently resonate with cosmic forces or divine attributes. This universal language of form allows the Yantra to transcend linguistic barriers, acting as a direct conduit for spiritual energy, irrespective of the specific script used for accompanying mantras. This systematic approach also highlights the intellectual and philosophical depth underlying the seemingly simple tattoo designs.

The four main forms of Yantra are:

|

Yantra Form |

Primary Symbolism |

Associated Deities/Concepts |

Key Benefits |

Relevant Snippets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Circular |

Unity, Integrity of the Universe |

Buddha, Lord Brahma |

Unity, Wholeness |

|

|

Triangular |

Triple Gem of Buddhism (Buddha, Dhamma, Sangha), Hindu Trinity (Shiva, Brahma, Vishnu) |

Buddha, Dhamma, Sangha; Shiva, Brahma, Vishnu |

Balance, Harmony |

|

|

Square |

Four Continents, Four Elements (Earth, Water, Wind, Fire) |

Earth, Water, Wind, Fire |

Stability, Structure |

|

|

Picture |

Virtues of Angels, Humans, Animals, Deities |

Angels, Humans, Animals, Deities (e.g., Hanuman, Naga, Ganesha) |

Specific Powers (e.g., protection, strength, charm, wisdom) |

Yantras serve a variety of purposes, broadly categorized into: protection and invincibility; popularity, love, and charm; fortune and wealth; general auspiciousness; prestige; and other specific desires.

B. Detailed Explication of Prominent Sak Yant Designs

The extensive lexicon of Sak Yant designs encompasses a rich array of symbols, geometric configurations, animal depictions, and divine effigies, each imbued with unique semantic and teleological significance. At least twelve prominent designs are detailed below:

- Hah Taew (Five Sacred Lines)

- Meaning: This is one of the most widely recognized and popular Sak Yant designs, often considered a foundational tattoo for new recipients. It comprises five vertical lines of magical inscriptions, with each line imparting a distinct blessing related to various aspects of life. Its power is believed to derive from the four elements: fire, water, air, and earth.

- Benefits: The first line offers protection against unjust punishment, provides favorable outcomes in ambiguous situations, purifies unwanted spirits, and safeguards the wearer’s living space. The second line works to reverse and protect against negative astrological influences and misfortune. The third line provides protection from black magic and curses. The fourth line energizes good luck, success, and fortune for future ambitions and lifestyle. The fifth line enhances charisma and attraction to the opposite sex, while also boosting the effects of the fourth line.

- Visual Characteristics: Typically consists of five vertical lines of ancient Khom script, often placed on the back, particularly the left shoulder or the base of the neck.

- Gao Yord (Nine Spires)

- Meaning: Known as the “Master Yant” or “Nine Peaks,” this design symbolizes the nine supreme qualities of the Buddha and represents the nine peaks of Mount Meru, the mythical abode of the gods. It is considered a highly sacred Buddhist tattoo, offering extensive protective powers.

- Benefits: It bestows inner strength, protection from misfortune, general luck, and success. Specific powers include invincibility against all weapons, popularity (Maeta Ma Hah Niyom), avoidance of serious injury (Klaeoklad), the ability to defeat enemies (Chana Satru), great power and authority (Ma Hah Amnat), the willingness to fight for loyalty (Awk Seuk), success in business ventures (Oopatae), improved destiny (Noon Chataa), immense good fortune (Ma Hah Lap), protection from accidents (Pong Gan Antarai), and enhanced career prospects (Nah Tee Gan Ngan Dee).

- Visual Characteristics: Features nine peaks or spires, typically positioned at the top of the back along the spine. The design incorporates three ovals representing the Lord Buddha and includes Khom script mantras at its base. A central “magic box” often contains a patchwork of small squares, each with a Khom abbreviation for protective spells.

- Prohibitions: To maintain its power, recipients are traditionally advised against insulting parents or teachers, spitting into toilets, engaging in sexual activity during a woman’s menstruation, oral sex, offending children or committing adultery, using drugs, consuming specific foods (zucchini, fang, licorice), passing under clotheslines, or sitting on ceramic urns.

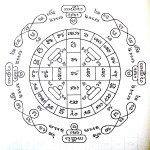

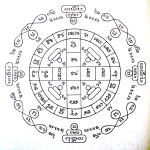

- Paed Tidt (Eight Directions)

- Meaning: Translating to “Eight Directions,” this Yant represents comprehensive protection from all eight cardinal directions of the universe. It features eight mantras arranged in concentric circles and eight distinct representations of the Buddha.

- Benefits: Primarily offers protection for travelers, safeguarding them from evil spirits and threats that may emerge from any direction, including above and below. It is revered for its all-encompassing strength.

- Visual Characteristics: A circular geometric design, typically tattooed on the center of the back. It prominently displays eight groups of three ovals, each symbolizing a different Buddha.

- Associated Chants: Specific Pali chants are associated with each direction of travel, such as “I Ra Cha Ka Tha Ra Saa” for the East.

- Yant Kroh Petch (Diamond Armor)

- Meaning: Literally “Diamond Armour,” this Yant is a powerful symbol of spiritual defense. Its design resembles a robust shield.

- Benefits: It is believed to provide an impenetrable sanctuary against dark spells, malevolent forces, negative energies, and maleficent spirits. It actively repels danger and harm, functioning as an invisible cloak that deflects perils from both the physical and ethereal realms, reflecting bad luck and dark energies back to their source.

- Visual Characteristics: A shield-like geometric design, often recommended for placement on the back to maximize its protective power. It is intricately inscribed with Khom script.

- Yant Phra Pidta (Closed Eyes Buddha)

- Meaning: “Buddha closes eyes.” This design depicts a monk with his hands covering his eyes, symbolizing profound indifference to external temper and emotions, fostering ultimate focus and inner peace. It is also interpreted as an evolution of the God of Fortune.

- Benefits: Offers comprehensive protection against dangers, obstacles, negative energies, black magic, and curses. It is believed to bring good luck and favorable opportunities, strengthen meditation practice, and promote peace of mind. Additionally, it is associated with prosperity and success, and for individuals in high-risk professions, it provides protection from external factors.

- Visual Characteristics: Typically an image of a monk seated in a half-lotus position with hands covering the eyes, sometimes depicted with multiple arms or adorned with other yant tattoos.

- Hanuman (Monkey God)

- Meaning: Hanuman is a mythical Monkey God from the Hindu epic Ramayana, revered for his extraordinary strength, unwavering courage, loyalty, and perseverance. In Thai culture, he symbolizes hope for humanity by demonstrating the ability to transcend worldly shallowness.

- Benefits: Bestows protection from danger, fearlessness in the face of adversity, strengthened self-confidence, the ability to influence others, enhanced focus, and determination to achieve goals. It also brings kindness (Maeta mahah niyom), protection from serious injury (Klaeoklad), the capacity to defeat enemies (Chana Satru), great power and authority (Ma hah Amnat), the courage to fight for loyalty (Awk Seuk), and magical invincibility (Kong Kra Phan).

- Visual Characteristics: Depicted as a monkey god, often in a dynamic, warrior pose, sometimes wielding a weapon.

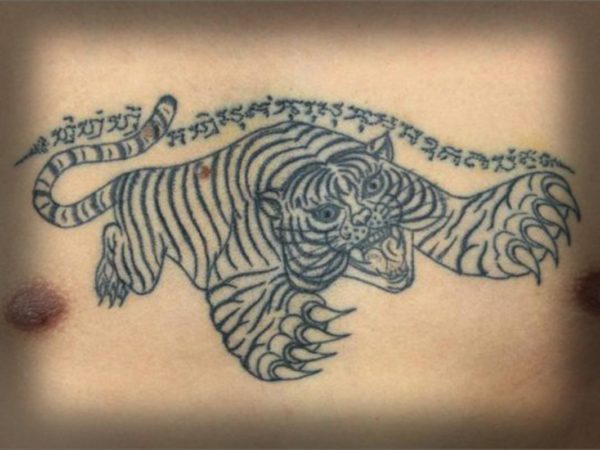

- Yant Suea Koo (Twin Tigers)

- Meaning: “Twin Tigers” or “Paired Tigers.” This design represents immense power, strength, and fearlessness, making it a popular choice among Muay Thai fighters and soldiers.

- Benefits: Provides strength, speed, agility, and the highest level of power attainable within Sak Yant magic. It offers robust protection against enemies and dangers, and is believed to bring Maha Amnaj (power over subordinates) and Serm Yos (improvement of status and promotion). It is also considered beneficial in business dealings for entrepreneurs.

- Visual Characteristics: Typically features two symmetrical tigers, often in a fierce stance, accompanied by traditional script.

- Naga (Serpent)

- Meaning: A serpent-like mythological creature, often depicted with a dragon’s head, the Naga is revered across many Asian cultures for its power, wisdom, and connection to spiritual forces. It is considered a guardian of hidden treasures and sacred teachings, and its association with water symbolizes purification and regeneration.

- Benefits: Offers protection from negative influences, attracts wealth and prosperity, inspires wisdom and intuition, fosters a deep spiritual connection, facilitates personal transformation, and promotes charm and popularity, encouraging mutual affection among people.

- Visual Characteristics: A serpent-like figure, frequently depicted with a dragon’s head, sometimes in an intertwined form (Nakkaew Yant).

- Ganesh (Elephant God)

- Meaning: A Hindu deity with an elephant head, Ganesh is revered for his wisdom, power, and protective qualities. He is considered the Lord of Beginnings.

- Benefits: Symbolizes success and the breaking down of obstacles, blessing new ventures, and imparting knowledge and wisdom. It inspires self-confidence and the ability to navigate hardships with grace and perseverance, bringing business and financial prosperity.

- Visual Characteristics: Depicts an elephant-headed, human-bodied deity.

- Yant Phaya Rachasi (King of Lions)

- Meaning: Translating to “King of the Lions,” this Yant symbolizes strength, courage, nobility, majesty, and dominance.

- Benefits: Bestows great power, authority, and control, earning respect from all. It inspires bravery, loyalty, and the capacity to protect loved ones, while also building self-confidence, determination, and leadership qualities. It is believed to bring success and respect.

- Visual Characteristics: Depicts a lion, often accompanied by a flag (symbolizing victory), as seen in the Yant Singh Thong.

- Unalome (Path to Enlightenment)

- Meaning: Represents the path to enlightenment in Buddhist culture. The intricate spirals symbolize life’s twists and turns, struggles, challenges, and distractions, while the culminating straight line signifies the moment of achieving enlightenment, peace, and harmony.

- Benefits: Provides spiritual guidance, protection, luck, and success. It is also believed to highlight and strengthen the individual blessings conferred by other Sak Yant designs.

- Visual Characteristics: A distinctive spiral pattern that typically begins at the base, spirals and zigzags upwards, and culminates in a straight line at the top. Variations include double spirals, moon unalomes, inverted unalomes, floral unalomes, and dotwork unalomes.

- Yant Sarika (Magic Bird)

- Meaning: Depicts a magic bird, often a songbird, associated with enchanting communication and deep-seated love in Thai mythology. It is believed to possess the ability to mimic sounds, rendering its voice captivating and persuasive.

- Benefits: Facilitates improved communication and contacts, enabling easy connection with people, and brings good luck in love affairs. It also attracts money, enhances charm, fosters kindness, and increases popularity. The Yant is believed to provide an advantage in disputes and negotiations.

- Visual Characteristics: Depicts one or two Sarika birds, often accompanied by traditional script.

- Yant Jing Jok (Gecko)

- Meaning: The gecko is believed to embody virtues that enhance attractiveness, loving kindness, and good luck. It is considered highly auspicious and is thought to attract business luck, customers, or love. This belief predates Buddhism, where finding a gecko was seen as a favorable omen, as they were thought to ward off evil spirits.

- Benefits: Increases attractiveness, kindness, popularity, and general luck, particularly in attracting money, customers, or romantic partners. It is considered beneficial for shopkeepers and gamblers.

- Visual Characteristics: Depicts a gecko, often with two tails, and typically features a Kata (mantra) inscribed along its back.

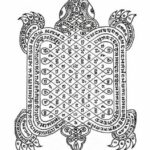

- Yant Tao Ruean (Turtle House)

- Meaning: According to legend, the Buddha was once incarnated as a turtle that grew to the size of a dwelling, hence the name “Tao Reun” (turtle house). The turtle is considered a fortunate animal in Chinese customs and symbolizes the planet and the earth element.

- Benefits: Bestows wealth, success, great luck, and a long life. It is believed to aid in the alleviation of emotional suffering, embodies perseverance, facilitates recovery from illness, and promotes the recognition of one’s own limits and respect for others’ boundaries. It provides physical defense and fosters independence.

- Visual Characteristics: Depicts a turtle, often with traditional Sak Yant script and patterns.

-

- Yant Paed Tidt with Tiger in Center

- Yant Suea Koo Ajarn Noo Kanpai

- Yant Takror

- Yant Paetch Payatorn

VI. The Sacred Scripts: Khom Agkhara and Regional Linguistic Variations

The spiritual efficacy and esoteric nature of Sak Yant are deeply intertwined with the ancient scripts employed in their inscription, which extend far beyond standard modern languages.

Kata Na Moe Put Taa Ya

A. Khom Agkhara: Origins, Structure, and Esoteric Significance

Sak Yant tattoos do not utilize standard Thai or Cambodian text; rather, they draw upon significantly older forms of language. The primary script used is Khom script (อักขระขอม), also known as Old Khmer or Khom Thai script. This script is derived from the ancient Brahmi script of India and was extensively used in Cambodia from the 7th to the 15th centuries for religious texts, temple inscriptions, and royal decrees.

Ancient Khom Agkhara in a grimoire from Mukhdaharn, which is based in ‘Horasart’ (Astrology)

The Thai language adopted the ancient Khmer script around the 10th century, later incorporating additional letterforms to better suit the Thai phonology. In the context of Sak Yant, Khom script is employed to write mystical incantations and magical symbols, which are believed to imbue the tattoo with spiritual energies. The characters themselves are often abbreviations for Kathas (mantras or prayers). Khom script is considered sacred, and its knowledge is often kept secret and guarded, reinforcing the esoteric nature of the practice.

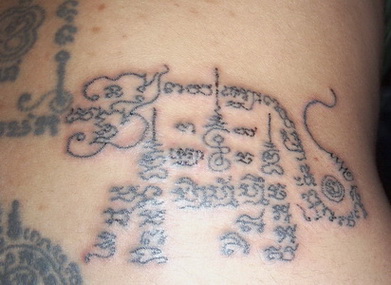

This is a tiger tattoo using sacred Khom Agkhara lettering called; Paya Suea Agkhara.

The deliberate use of ancient, non-colloquial scripts like Khom is not merely a historical artifact but a functional mechanism for preserving the esoteric nature and perceived potency of Sak Yant. By rendering the script largely unintelligible to the uninitiated, it reinforces the authority and spiritual power of the masters, transforming the textual component into a sacred, almost alchemical, element rather than a readily decipherable message. This linguistic barrier acts as a “gatekeeper,” ensuring that the spiritual power remains exclusive to the initiated and is not diluted by widespread, unceremonious understanding.

B. Regional Scripts: Pali, Lanna, Tham Isaan, and Their Role in Sak Yant

Beyond Khom, other ancient scripts play significant roles in Sak Yant, often reflecting regional variations and distinct lineages.

- Pali: An ancient Indian language, Pali serves as the liturgical language of Theravada Buddhism, which is dominant in Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka. It is frequently used in Sak Yant tattoos for sacred prayers, mantras, and invocations, believed to harness spiritual power and provide protection.

- Lanna Script (อักษรธรรมล้านนา / ตั๋วเมือง): Predominantly used in Northern Thailand, this script is adapted from the ancient Mon script. Northern Thai masters often consider it more powerful and aesthetically pleasing. Lanna script comprises 43 consonants, two types of vowels (independent and dependent), and two tone marks. It was historically used for writing Northern Thai (Kam Mueang), Tai Lue, Tai Khün, Lao Tham, and Buddhist religious languages such as Pali and Sanskrit.

- Tham Isaan Script (อักษรธรรมอีสาน): An ancient script used in the Isaan (northeastern) region of Thailand, Tham Isaan script is fundamental for inscribing Yantras in this area and is deeply embedded in its cultural and traditional practices. It is associated with specific Yantras such as Maha Ut (invulnerability), Na Setthi (wealth), Itipiso (directional protection), Suea (tiger for abundance), and Namo Phutthaya (protection during travel).

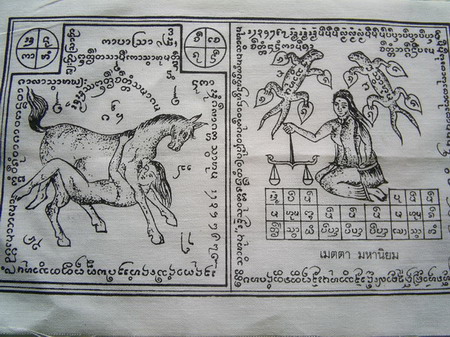

Pha Yant Lanna Ma Saep Nang

Other scripts, including Lao, Burmese, Mon, Tai Lu, Shan, and Lao Tham, are also found in Sak Yant depending on the specific region and lineage.

The variation in scripts across regions—Khom in Central Thailand and Cambodia, Lanna in Northern Thailand, Tham Isaan in Northeastern Thailand, and Pali in Southern Thailand—indicates that Sak Yant is not a monolithic practice but rather a culturally adaptive one. This linguistic diversity serves as a significant marker of regional identity and local spiritual traditions. It suggests that the power of the Yant is not solely universal but also profoundly rooted in specific cultural and historical contexts, resonating with localized beliefs and ancestral knowledge. This localized power strengthens the connection between the practitioner, the recipient, and their immediate cultural environment, making the practice deeply personal and culturally resonant within each region.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Sak Yant Scripts

|

Script Name |

Historical Origin/Derivation |

Geographical Prevalence in Sak Yant |

Primary Use in Sak Yant |

Key Characteristics |

Relevant Snippets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Khom |

Derived from ancient Brahmi script of India; variant of Khmer script |

Central Thailand, Cambodia, parts of Myanmar |

Mystical incantations, magical symbols, abbreviations for Kathas |

Brahmi-derived; sacred; esoteric; sharper serifs/angles than Khmer; retains antique features |

|

|

Pali |

Ancient Indian language (c. 5th century BCE); liturgical language of Theravada Buddhism |

Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, Sri Lanka (as liturgical language) |

Sacred prayers, mantras, invocations |

Ancient liturgical language; oldest complete collection of Buddhist scriptures (Pali Canon) |

|

|

Lanna |

Adapted from ancient Mon script |

Northern Thailand |

Mantras, Buddhist texts, legal documents, historical chronicles |

Adapted Mon script; 43 consonants; two types of vowels; two tone marks; used for Northern Thai (Kam Mueang), Tai Lue, Tai Khün, Lao Tham |

|

|

Tham Isaan |

Ancient script of Isaan region |

Northeastern Thailand |

Writing Yantras, sacred texts, spells (Kathas); associated with specific Yantras (Maha Ut, Na Setthi, Itipiso, Suea, Namo Phutthaya) |

Fundamental for Yantra writing in Isaan; deeply embedded in cultural practices; used for various specific Yantras |

Sak Yant Paed Tidt by Luang Pi Pant

VII. Conclusion: Enduring Cultural and Spiritual Significance

Wicha Sak Yant stands as a profound spiritual tradition, intricately woven from a syncretic blend of indigenous animism, Hinduism, and Theravada Buddhism. Its historical trajectory can be traced from its origins in the Khmer Empire, where it served as a protective art for warriors, through its formalization and widespread adoption in Siam. This rich historical evolution underscores its enduring adaptability and deep cultural roots.

Yant Kwang Hliaw Hlang

Beyond its aesthetic appeal, Sak Yant functions as a potent conduit for mystical energies, believed to bestow protection, strength, fortune, and spiritual guidance upon its recipients. The critical role of revered masters—both ordained monks and lay Ajarns—and the meticulous ritualistic application process are paramount to activating the tattoos’ inherent power. The use of esoteric scripts like Khom Agkhara, alongside regional variations such as Lanna and Tham Isaan, further reinforces the sacred and guarded nature of this knowledge, ensuring its spiritual potency remains undiluted.

The increasing global interest in Sak Yant, partly propelled by celebrity endorsement , presents a complex paradox. While this expanded recognition offers potential avenues for the preservation of the tradition, it simultaneously carries the risk of cultural appropriation and the dilution of its profound spiritual significance, particularly when performed by non-traditional artists or for purely aesthetic reasons. The imperative remains to emphasize the importance of seeking reputable practitioners—genuine monks or Ajarns—who possess a deep understanding of the sacred texts, rituals, and ethical guidelines that underpin Sak Yant. Organizations such as the Federation Khmer Sak Yant are actively engaged in efforts to preserve and promote the authentic practice. This ongoing cultural negotiation between tradition and modernity, local heritage and global consumption, will determine the future trajectory of Wicha Sak Yant, ensuring it remains a profound spiritual undertaking rather than merely a fashionable aesthetic.